Don’t Worry, Be Hoppy!

Spring has sprung, so let’s hop to it!

It’s easy to make pun of springtime running, simply because for so many, the long, cold, dreary winter days meant lots of treadmill running, and it’s got us bouncing off the walls. Fortunately for those in the northern hemisphere, the daylight is getting longer, and the temperatures are creeping their way up into T-Shirt and shorts range. For those in the southern hemisphere, the long, hot, humid, dog-days are becoming those gloriously crisp and clear days, and prime race weather means peak physical race condition! Unless we’re sidelined by injury, which unfortunately happens all too often.

As we have been saying (and will continue to say!), the Breath Runner Method is designed to help minimize injury by helping us refine our running biomechanics in a wholistic and sustainable way. We’ve discussed many parameters of this, from the cadence patterning power of the 9-Step and 7-Step patterns when running at low effort levels, to the foundations of training structure. Now we’re going to dive deeper into the analysis of running gait, the importance of developing a robust and energy efficient stride, and how our tendon-muscle units in our legs work to propel us forward. Additionally, we’re going to explain scientifically validated methods for strengthening our bones, ligaments, and tendons so that our muscles can produce as much power as possible, while keeping the whole assemblage happy.

When we run, the movement of our legs goes through two distinct phases, alternating right and left: the Stance phase, characterized as one foot is on the ground, and the Swing phase, also known as the Flight phase, during which the both feet are off the ground.

Researchers describe how running is dependent on what is known as the ‘stretch-shortening cycle’ (SSC) of the musculotendinous unit, which they describe as an eccentric (stretch) phase, followed by an isometric transitional period (amortization phase, where the energy stored up from the eccentric phase stabilizes), leading into an explosive concentric (release) phase. A more common name for the stretch-shortening cycle is plyometrics. Professor Yuri Verkhoshanski, a well‐known track and field coach in Russia, is credited with starting the training concept that he referred to as ‘shock training’ or ‘jump training’. It was two-time Olympian Fred Wilt who, in 1975, first coined the actual term plyometrics. He combined the Greek words plythein (to increase or augment) or plyo (more), and metric, which means to measure. Therefore, plyometrics may be thought of as a way “to increase the measurement.” Increasing the measurement(s) in sports performance outcomes, whether it be throwing, serving velocity (as in tennis), jump height, or running speed, is the ultimate goal of any training program. Understanding plyometric’s role in such performance is crucial. In order to do that, understanding the basic biomechanics of running is fundamental.

———-

Want to read the rest of this journal entry? Join the Breath Runner Club and enjoy full journal entries, videos, and more!

Not ready to commit, but still want to help? Buy Me A Coffee!

Warming up to Warm Ups

On a topic like stretching, we think it’s best to begin by asking: How does this end? What’s the End Goal? Is it to become more flexible? Is it to prevent injuries? Is it to enhance performance?

It’s not a question of If; it’s a question of What When Why and How

Before heading out for a run, it’s always a good idea to do some stretching in order to get the muscles ready, right? Wellllll, not exactly. There’s been quite a kerfuffle the last few years (upwards of 20!) over the role of stretching and its effects on performance. Fortunately, researchers have taken the data, sifted and strained it through rigorous analysis, and a solid consensus among the experts has been reached. And if you believe that, I’ve got a bridge to sell you.

Here at Breath Runner, on any subject we look into, what we like to focus on is the WHY. Why does this [thing] do what it does? And then we do our research to find those answers. The problem is, there are often gaps in research, conflicting results between studies, and (usually) research which is myopically focused on one specific part (often microscopically) of what actually is a enormously complex, variable, and interconnected structural, biological, and neurological network of task-specific synergies. Think about it: human beings are just an assemblage of calcium-phosphate sticks, bound together with collagen tape and protein strings, wrapped up in a celluloid scrim to hold a massive amount of liquified protoplasm in a tensioned state while we consume a trifecta of chemicals which we use to propel ourselves forward, in hopes we will be able to flaunt a “26.2” sticker on our car’s bumper. Sometimes it’s tough to make it make sense.

On a topic like stretching, we think it’s best to begin by asking: How does this end? What’s the End Goal? Is it to become more flexible? Is it to prevent injuries? Is it to enhance performance? The researchers apparently agree, as they’ve asked these various questions, and they have found answers. To the question, “Does stretching make us more flexible?”, the answer is: It depends. To the question, “Does stretching prevent injuries?”, the answer is: It depends. To the question, “Does stretching enhance performance?”, the answer is: It depends. Stretching has its place; of that there is no doubt. It’s a matter of determining where that ‘place’ is, and how it fits into the Gordian knot of programming that is run training.

Image from: Running Forward, Glenn C. Rowe, PhD, Adeel Safdar, PhD, and Zolt Arany, MD, PhD. ©2025 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

We think it’s best to start examining the conundrum from the beginning. Here we turn to what we’ve already written about the role of the muscles as they relate to the movement of joints. As it pertains to freely movable skeletal joints, our skeletal muscles have three jobs.

JOB ONE: Protect the joint

JOB TWO: Stabilize the joint

JOB THREE: Move the joint

Think about that for a moment: while the primary purpose of skeletal muscles is to move bones, movement is its lowest priority. Another way of thinking about this is that in order for the ‘freely moveable joints’ to actually move freely, the surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments need to be (1) strong, (2) resilient, and (3) happy.

Now the question becomes, How do we achieve this? To stretch or not to stretch; that is the question. Welcome to the world of research Rabbit Holes. Ask one question, get a thousand conflicting answers. Ultimately, some calmer voices and a bit of common sense helps elucidate the core issues, and there actually seems to be some semblance of agreement on what needs to be done, when it needs to be done, and how it needs to be done.

Want to read the rest of this journal entry? Join the Breath Runner Club and enjoy full journal entries, videos, and more!

Not ready to commit, but still want to help? Buy Me A Coffee!

Ready to give the Breath Runner Method a try?

Training plans are available exclusively on TrainingPeaks!

Feel free to contact us for more information!

The Ties That Bind

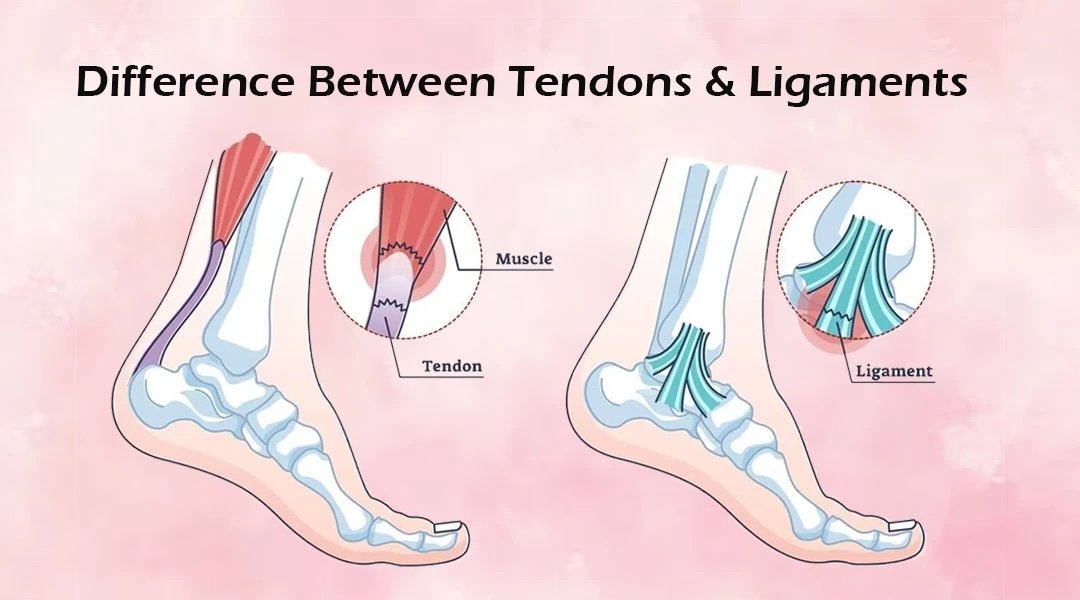

Last week we talked about bones, bone repair, and the role that the Breath Runner Method can play in helping minimize damage to the bones and maximize bone health. To re-cap: when we run, we move bones. The faster those bones move, and the larger the range of movement for certain bones (primarily in the legs), the faster we can run. How does our body manage to keep all of these mostly rigid, bony ball and socket structures in place and moving appropriately? This is the role of our tendons and ligaments.

Tendons & Ligaments & Sinew, Oh My!

Last week we talked about bones, bone repair, and the role that the Breath Runner Method can play in helping minimize damage to the bones and maximize bone health. To re-cap: when we run, we move bones. The faster those bones move, and the larger the range of movement for certain bones (primarily in the legs), the faster we can run. How does our body manage to keep all of these mostly rigid, bony ball and socket structures in place and moving appropriately? This is the role of our tendons and ligaments.

Copyright © 2025 3D4Medical Ltd., its licensors, and contributors. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

As we have mentioned before, both tendons and ligaments are types of connective tissue in the body, but serve different functions. Tendons are tough, fibrous bands of tissue (not unlike a climber’s rope) that connect muscles to bones. Tendons transmit the force generated by muscles to the bones. When bones move in a coordinated fashion, movement occurs. Tendons are composed primarily of collagen, a protein that provides strength and elasticity.

© Copyright 2025 Frontiers Media S.A. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

Ligaments, while also tough, fibrous bands of tissue, connect bones to other bones. They provide stability to joints by limiting their range of motion and preventing excessive movement. As with tendons, ligaments are also composed primarily of collagen. Imagine if we took a classroom skeleton, and at pretty much every place where two bones meet, we duct-taped them together. From the tiny bones at the tips of the fingers to the big ball and socket joints in the hip and shoulders. That’s pretty much the way ligaments behave, albeit with quite a lot more finesse, mobility, and utility.

What’s important for us as runners to understand is that while both tendons and ligaments are critically important for proper body movement, and they are extremely resilient, they can still get damaged. Tendons tend to get injured when there is an over-stretching of the fibers, commonly known as strains, while ligaments are more prone to things like sudden, extreme twisting movements, widely known as sprains. Of course, both are subject to acute damage from impact injuries, but we’re going to focus more on the chronic injuries, which occur slowly over time, progressively getting worse and worse. In worst-case scenarios, either acute or chronic, the fibers could get torn completely, requiring surgery to repair them.

A leading researcher in tendon/ligament studies, Dr. Keith Baar of the University of California Davis, says, “[The] tendon has long been undervalued. Most textbooks describe only one concept of this tissue: tendons attach muscles to bones. This is akin to saying that Michelangelo was a painter. Both statements are true, but do not even begin to describe the importance of their subjects. In attaching a compliant tissue to a stiff one, tendon has a very difficult mechanical role: overcoming impedance mismatch. Impedance mismatch occurs when two mechanically different tissues are joined, resulting in strain concentrations where injury is most likely to occur.” He further explains that “Tendon mechanics are not uniform; rather they have regional differences in stiffness along their length, ranging from compliant at the proximal (muscle) end to stiff at the distal (bone) end.” This has HUGE implications for us as runners.

Let’s think about one of the most notorious injury-prone tendons for runners, the Achilles tendon, or as it’s formally known, the Calcaneal tendon. It’s the strongest and thickest tendon in the entire human musculoskeletal system. One of its unique features is that it’s one tendon for TWO muscles; the gastrocnemius and the soleus, which together are referred to as the triceps surae. The Achilles tendon attaches on the foot to the calcaneus (heel) bone. Achilles tendinopathy, which is a catch-all term describing degenerative changes of the tendon (ranging from mild inflammation to a literal shredding of the tendon fibers), is one of the most common sports injuries, and accounts for 8–15% of all running injuries. More on this in a moment.

When we run, the mechanical movement of the foot and leg bones are controlled by the muscles throughout almost the entire body (literally from the neck down). Yet if the muscles alone had to do all the work of moving bones, we wouldn’t get very far, and wouldn’t be very fast, if we could move at all. The tendons play a unique role in animal locomotion in that they provide for both the storage and release of elastic energy provided by the muscles. Dr. Thomas J. Roberts, of the University of Oregon, explains, “During activities that require little net mechanical power output, such as steady-speed running, tendons reduce muscular work by storing and recovering cyclic changes in the mechanical energy of the body.” In other words, we can run because we have built-in springs in our legs. This natural load and recoil action of the tendons, especially the Achilles tendon, gives us a higher level of energy efficiency, which minimizes fatigue of the muscles attached to the tendon. It is thought that fatigue minimization may be one of the primary evolutionary principles driving human gait selection.

The problem with all this loading and recoiling of the Achilles tendon for runners seems to be the rate at which it happens, especially in relation to our individual level of fitness. When we look at the tendon under a microscope, we will see individual collagen fibrils, with a host of other protein-based material, all bundled together in what is known as the ExtraCellular Matrix (ECM). As shown in the illustration above, these fibrils combine to form fascicles, which combine to form the tendon itself. Note that there are similar terms which has relevance to this discussion: fascia, the connective tissue that permeates every part of our body, and sinew, which is basically tendon tissue that runs within the muscle. Fascia and sinew fibers are integral to the make up of tendons, with fascia wrapping itself around each and every strand, unit, and the entire tendon itself, and sinew being the integration of tendon and muscle fibers.

Biological tissues such as tendons are viscoelastic, which means they possess both elastic and viscous (liquid-like) properties. Viscous materials (like water) when stressed, resist both shear flow and strain in a one-dimensional direction over time. Elastic materials strain when stretched, then return to their original state once the stress is removed. Think of a rope; when a load is attached, the rope will elongate in one direction. The bigger the load, the greater the stretch, but the amount of stretching gets resisted in a exponential fashion. At first, the rope stretches easily, but as it grows taut, it gets harder and harder to gain any length. Now release the load off of the rope suddenly, and the rope will recoil (possibly violently), until eventually returning to it’s original length. The difference between a tendon and a rope is the liquid component. When tendon fibers get stretched, the liquid which acts as a lubricant within the individual collagen fibrils and between the fascicles gets squeezed out in a process known as collagen denaturation. You could see this in action with a wet rope of natural fiber. Stretch it taut and you’ll see the water droplets form and drip off the rope.

Dr. Baar explains that this viscoelastic trait has several important consequences for tendons:

Want to read the rest of this journal entry? Join the Breath Runner Club and enjoy full journal entries, videos, and more!

Ready to give the Breath Runner Method a try?

Training plans are available exclusively on TrainingPeaks!

Feel free to contact us for more information!

“Why Breathing Frequency May Become Our Best Measure of Training Stress”

Injuries happen. What’s important for us as runners is knowing how to properly recover so that we don’t make things worse in the meantime. Often, this is far easier said than done. For me, I knew that at an absolute minimum, a bone needs six weeks to heal from a fracture. This is both a biochemical and a mechanical process which, if allowed to run its course, can actually make the bone stronger than it was before!

This isn’t news to us, but glad to see that some of the top exercise physiologists are getting the data to prove what we’ve been saying!

https://www.fasttalklabs.com/fast-talk/why-breathing-frequency-may-become-our-best-measure-of-training-stress/

A Bone To Pick

Injuries happen. What’s important for us as runners is knowing how to properly recover so that we don’t make things worse in the meantime. Often, this is far easier said than done.

Want to make bone jokes, but don’t knee-d to.

I broke my foot last year while out on a trail run. Something caught my toe and threw me off-balance; I tried to stay up, but my left foot landed in a slight depression. Since I was off-balance to begin with, my FULL weight, plus the force of gravity, combined to flex my foot downward, and my running sneakers — not Trail Running sneakers (lesson learned) — that I was wearing allowed that flex to happen. Spiral fractures of the fourth and fifth metatarsals were the result.

Approximately twelve weeks later, I was able to run again. 20 minutes of pain-free treadmill. Approximately 10 weeks later, I completed an Ironman 70.3. My secret? I did NOT try to run while my foot was healing. Not even a little bit. After 3 weeks, I began to swim a little. At about four weeks in, my doctor cleared me to start walking. I added in some stationary cycling shortly afterwards, as well as kayaking and paddle boarding. I waited for the doctor to clear me for outdoor riding, and then continued to ever so slightly increase time and effort, always wary for the slightest sign of discomfort or swelling, which fortunately never appeared. Finally the day came when the doctor said I was good to go, and that’s when I got on the treadmill. First for 20 minutes, then within a week up to 30 minutes. 40 minutes, 45, 50; tiny, incremental increases in distance surrounded by all the other cross-training.

Injuries happen. What’s important for us as runners is knowing how to properly recover so that we don’t make things worse in the meantime. Often, this is far easier said than done. For me, I knew that at an absolute minimum, a bone needs six weeks to heal from a fracture. This is both a biochemical and a mechanical process which, if allowed to run its course, can actually make the bone stronger than it was before! Fracture healing is complex, and has four distinct stages: the first, which occurs immediately after fracture, is the hematoma formation (bruising and blood clotting). Then after a few days (up to two weeks), is the granulation tissue formation, creating a spiderweb-like collagen-rich fiber network across the fracture, which starts the process of regaining bone integrity. That is followed by what is known as callus formation, where endochondral ossification, or the process of turning the collagen fibers into calcified immature bone, takes place. This ossification descends from the surface into the deep cavern the fracture created, and also allows for the capillarization of the bone tissue (the blood flow through the bone tissue) to be re-established. The length of time for this process can vary widely, depending one how deep the fracture was, or in the case of a complete break, exactly how big the bone was, and whether the break is displaced. This is a critical process which can not be rushed! Finally, there is bone remodeling, or the process where the immature bone regenerates into normal bone structure. This remodeling can take months in some cases.

A bone injury to the foot is never a simple thing. The foot has 26 bones, 33 joints, and 4 layers of muscle, all strapped together in a package that is only (on average, males) 293mm long, 72mm high, and 104mm wide. Those 26 bones carry the weight of another 180 bones and everything that is attached to them. Screw around with the healing process of the bones of the foot (or any other bone, for that matter) at your own peril. Taking care of our bones needs to be a priority.

Want to read the rest of this journal entry? Join the Breath Runner Club and enjoy full journal entries, videos, and more!

Ready to give the Breath Runner Method a try?

Training plans are available exclusively on TrainingPeaks!

Feel free to contact us for more information!

Conditioning for Strength

You can’t fire a cannon from a canoe

It’s impossible to go onto social media anymore without some advertisement or some influencer boasting about the latest, greatest strength hack, exercise, or stretch that promises to transform your entire world. It’s beyond exhausting. So we’ll start out acknowledging that we’re going to attempt to be the proverbial finger in the disinformation dike, despite the waves crashing over the top of the dam.

Runners need to be strong. We all know this. What most don’t know is: How strong is strong enough? Is there a “right way” to be strong? What exercises for what effect, and how do they fit into an already demanding run training schedule? We’ve spent a lot of time learning from some of the world’s best coaches, and feel confident that we can answer all of the above questions with the most appropriate, world-class answer: It depends.

Let’s start with one of our biggest pet peeves: the need to vary exercises in order to ‘confuse the muscles’. Let’s stop for a moment and consider this statement. Let’s pick the bicep muscle (which is actually two: there’s the long head of biceps brachii, and the short head). Now: Confuse it. Confuse the bicep muscle.

Image found on Internet without attribution

The bicep is made up of over two hundred fifty thousand individual muscle fibers. Each muscle fiber has two actions which it can perform: One: contraction; and Two: relaxation. Confuse that. The physiological concept of muscle contraction is based on two variables: length and tension. There are four basic types of skeletal muscle contractions: concentric, isometric, isotonic, and eccentric.

Concentric contraction is when the muscle contracts and shortens (such as a biceps curl or standing from a squatting position).

Isometric contraction is a change in muscle tension without a change in muscle length (as when pushing against an immovable object).

Isotonic contraction is a constant muscle tension with a change in muscle length (such as walking, running, or squatting).

Eccentric contraction is when the muscle resists extension (such as slowly coming down after a pull-up or during downhill walking). Eccentric contractions act as a braking force in opposition to a concentric contraction to protect joints from damage.

OK, so all that can be a little bit confusing. But is it the muscle fiber, or us, which is confused?

Want to read the rest of this journal entry? Join the Breath Runner Club and enjoy full journal entries, videos, and more!

Ready to give the Breath Runner Method a try?

Training plans are available exclusively on TrainingPeaks!

Feel free to contact us for more information!

Aerobic vs Anaerobic

There’s so much noise around the various parameters of run training that it’s easy to have the very basics lost in the confusion. What pace? Which zone? What heart rate? One of the very basic things which we think gets lost is the difference(s) between aerobic and anaerobic efforts. Follow along as we de-tangle myth from legend.

To breathe, or not to breathe; that is the question

There’s so much noise around the various parameters of run training that it’s easy to have the very basics lost in the confusion. What pace? Which zone? What heart rate? One of the very basic things which we think gets lost is the difference(s) between aerobic and anaerobic efforts. Follow along as we de-tangle myth from legend. We’ll try to keep things simple, but understand that while the What’s and How’s of these parameters may be relatively simple, the Why’s can get very complex.

Aerobic: from the Greek words “aero”, (air) + “bios” (life). The word is often credited to scientist Louis Pasteur who, in 1863, defined it as, “able to live or living only in the presence of oxygen, requiring or using free oxygen from the air," (Note: he was referencing certain bacteria)

Anaerobic: Same as above, but adding in the Greek “an” (without). Pasteur defined it as “capable of living without oxygen.” (Same note applies)

Without a doubt, we are aerobic beings. We need oxygen to live. So why is there so much discussion about anaerobic exercise? If not breathing means dying, why would we want to go anaerobic?

The simple answer is that nature designed us this way. There are VERY short periods of time when our muscles can contract without having to utilize oxygen in the process. These are quick, powerful bursts of energy, meant to maximize force production. So, for our running, the simplest way to think about this is:

Aerobic exercise: Training which primarily conditions the heart (which it is often referred to as “cardio”, short for cardiovascular), such as running or cycling. We can sustain this level of exercise for a prolonged period of time (many minutes up to hours), depending on the rate of exertion and the individual’s adaptation to the activity.

Anaerobic exercise: Strength and power, such as weight lifting or High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT). This level of exercise can only be sustained for very short durations (seconds to minutes), depending on rate of exertion and the individual’s adaptation to the activity.

Let’s set some ground work by doing a shallow dive into the chemistry of all of this. This can easily get confusing and overwhelming, but it’s important to understand the biological imperatives in order for us to make sense of the What’s and How’s of our training.

At its most basic, our muscles favor cellular aerobic respiration. Here’s what that looks like from a scientist’s point of view:

C6H12O6 + 6O2 → 6CO2 + 6H2O + 38 ATP (energy)

Here’s what that means: our muscle cells take one molecule of glucose (C6H12O6, the most elemental form of sugar), and six molecules of oxygen (O2), in order to create the energy needed to move the muscle fibers. This process is known as the Krebs Cycle. Of course, there’s a whole lot more going on in this process; feel free to follow that hyperlink to dive into the details if you so choose. A key to this process is the creation of the molecule called adenosine triphosphate, or ATP. ATP is the body’s energy fuel source of choice. It is a highly charged (ionized) molecule. Due to its negative charge, ATP’s chemical bonds can store a large amount of energy, which can be liberated easily within the muscle cell’s mitochondria, the “power factory” where all this ensorcelled chemistry occurs. In aerobic respiration, when each glucose molecule gets broken down, and when combined with those six oxygen molecules, the reaction creates 38 ATP molecules.

We’re keeping it simple, so we’re continuing on — the end result of this combustion is a release of six molecules of carbon dioxide (CO2) and six molecules of water (H2O), along with the energy (38 ATP) needed to actually do the work. This is considered a very metabolically efficient process, since the end “waste” products are nothing more than carbon dioxide and water, which our bodies are well equipped to get rid of. One of the nice things about this process is that while muscle glycogen (glycogen being two or more linked molecules of glucose) is relatively limited in quantity, our body has large reserves of glycogen stored away in the liver. When we’re operating in the aerobic zone, our body can tap into these reserves, and use these to fuel the operation. Additionally, it’s really easy for us to ingest something with a lot of carbohydrates (like a sports drink), which replenishes a proportion of the balance, allowing us to operate for long periods of time. Something to keep in mind, however, is that it takes a relatively long time to pull glycogen out of the liver and get it into the muscles.

Of course, there is a LOT more going on in the muscles than this simple formula, and this is why it’s so easy to get swamped with seemingly contradictory information. We’ll get into all of that in a moment. First, let’s talk about anaerobic respiration, a.k.a, Glycolysis. Here’s the chemical formula:

C6H12O6 + 2 NAD⁺ + 2 ADP + 2 Pᵢ → 2 Pyruvate (C3H4O3) + 2 NADH + 2 H⁺ + 2 ATP + 2 H₂O + energy

So again we’re starting with one molecule of glucose, but this time we’re adding in two molecules of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), an essential “coenzyme”, or an organic non-protein compound that binds with an enzyme to catalyze a reaction; two molecules of adenosine diphosphate (ADP), another essential organic compound found in living cells which has an essential role in the energy flow of cells; and two molecules of inorganic phosphate (Pi), which is required by the body for things like energy metabolism, signal transduction and pH buffering. Notice that the only oxygen in this formula is that which is bound up within glucose. The mitochondria crunches these components together into an explosive amalgamation which results in two molecules of pyruvate, a transport molecule which carries carbon atoms to and from the mitochondria; two molecules of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (a positively charged version (NAD⁺) goes in, and an uncharged version (NADH) comes out); two charged hydrogen atoms (also known as hydrogen ions); two molecules of water; and two molecules of ATP. There’s an additional two molecules of ATP created in this process (not shown), for a total of 4 ATP.

So simple, right? Here’s the take-away: *IF* we keep our effort levels relatively low and controlled, we can utilize the aerobic process and create 38 ATP, and clean up is easy. Once we start exercising at a level where the demands for energy in the muscles becomes so severe that they can no longer sit around and wait for the aerobic process to pull in all those energy-rich oxygen molecules and re-package them into clean little CO2 and water molecules, the mitochondria starts grabbing less energy-dense but more readily available organic compounds, smashes them together to break them into little firecrackers of energy. This is a messier process (as you may have noticed from the above chemical formula), which only gives us 4 ATP. Less bang for the buck, but the needs are exponentially higher, and the time it takes to get that energy is reduced, which is why this metabolic “short-cut” gets used. The resultant waste products get dumped out into the bloodstream faster than the liver, kidneys, and other cells can clean them up, and the increasing number of hydrogen ions acidifies the blood plasma.

Want to read the rest? Join the Breath Runner Club!

Not ready to commit, but still want to help? Buy Me A Coffee!

Training plans are available exclusively on TrainingPeaks!

Feel free to contact us for more information!

Gimmicks, Devices, & Pseudoscience, Oh My!

One of the things that Breath Runner has tried very hard to do is to ensure that we can back up everything we’re saying with reliable sources. It’s a challenge, as the Breath Runner Method has no “direct” peer-reviewed research. It’s a new concept, even if it’s based on an old — VERY old! — idea.

Don’t get caught in the Monkey Trap

One of the things that Breath Runner has tried very hard to do is to ensure that we can back up everything we’re saying with reliable sources. It’s a challenge, as the Breath Runner Method has no “direct” peer-reviewed research. It’s a new concept, even if it’s based on an old — VERY old! — idea. People have been syncing cadence to breathing patterns ever since Armies learned how to march in formation. For runners, this entrained method of cardiorespiratory locomotion (as the scientists like to call it) is a fundamental, evolutionary aspect of running. Researchers at the Department of Integrative Physiology, University of Colorado, Boulder, state, “Humans naturally select several parameters within a gait that correspond with minimizing metabolic cost.” However, in that very report, the study participants were pretty much evenly divided between how they chose between minimizing metabolic energy, minimizing movement time, or none of the above (could not be explained by minimizing a single metabolic cost). So what does this mean for us? It means, essentially, that running is a complex activity, and there is not a single, ultimate “right way” to run that works for everyone.

Equally confounding is the fact that there is so much scientific, peer-reviewed research out there that it’s extremely easy to cherry-pick through papers which adhere to one’s pre-conceived notions; also known as Confirmation Bias. One area which is rife with such abuse is in the diet and nutrition realm. To help address this, the International Food Information Council published a paper called, “10 Red Flags Of Junk Science”. They created this list to help “anyone determine the credibility of scientific findings.”

Recommendations that promise a quick fix.

Dire warnings of danger from a single product or regimen.

Claims that sound too good to be true.

Simplistic conclusions drawn from a complex study.

Recommendations based on a single study.

Dramatic statements that are refuted by reputable scientific organizations.

Lists of “good” and “bad” foods.

Recommendations made to help sell a product.

Recommendations based on studies published without peer review.

Recommendations from studies that ignore differences among individuals or groups.

We welcome anyone to go through our website and find were we may have strayed from these ten points. If we have, we will correct it and publicize that correction. We have reached out to researchers and medical professionals asking for their thoughts and corrections; to date, no one has taken issue with anything we have said or how we have said it. In fact, one doctor not only reviewed the website, they became a Breath Runner! Here is an actual text message we received from them:

* “How do people run long…” is what they meant to say.

It’s not just us that’s concerned with the ‘infotainment influencers’ who boast the greatest training methodology, or nutritional supplement, or other wellness ‘hacks’. Rick Prince, founder of United Endurance Sports Coaching Academy (UESCA), a science-based endurance sports education company, just published an article entitled, “Beware of Shiny Objects.” The same day that hit my inbox, I got another email from Dr. Peter Attia, promoting a video on his YouTube channel entitled, “Why rate of perceived exertion (RPE) is the best metric for identifying Zone 2 training”. We really enjoyed both of these, not only because they are full of excellent information from highly regarded experts, but also because they basically were echoing things we had already written! We talked about the “Shiny Object Syndrome” (not an actual syndrome, and not exactly what we had called it) in our post New Year, New You. And we talked about the variations and vagaries of Zone 2 in our post entitled (*ahem*): Zone 2.

More than just that, though; both emails, for me, were cautionary tales of blindly following the latest piped piper off the cliff. Both of these experts were saying, in principle, that the most important thing we can do as runners, as athletes, is for us to do our own due diligence and find those things — whether they are devices, metrics, or foodstuff — which work for us, individually. I’ve long since lost count of the number of posts I’ve seen on social media by people honestly inquiring what their “correct” heart rate should be for this Zone or that. And many well-intentioned people (often numbering in the hundreds) respond with well-known tropes such as “220 minus age” as a way to determine the “correct” heart rate. There’s just one problem with that formula: it doesn’t work for individuals. It is meant for age-group populations. It may well get you a ball-park estimate of your heart rate zones, but then again, that ball park may be in a completely different city from the one you live in. The only way to know for sure what your *exact* heart rate parameters are is to undergo a metabolic test under the supervision of a qualified medical expert or coach certified to conduct such tests. Even then, as we have previously written, there are literally dozens of influences, both internally and externally, which can change the numbers on a day-to-day or even an hour-to-hour basis.

One of the primary areas of focus for us, and one of the foundational principles of the Breath Runner Method, is the strengthening of the respiratory muscles through the process of running with deep, controlled breaths. Again, syncing run cadence to breathing is not new. It’s been around for a LONG time. And it’s a proven concept of using breath patterns to sustain high effort running, especially sprinting. We like to think that our contribution to this august lineage has been the addition of the long breath patterns, the 7-Step and 9-Step patterns. To our knowledge, this has never been used as part of a systematic training protocol. Again, if anyone has knowledge of this, let us know and we will correct our statements. It should be noted that when we first came up with the Breath Runner Method, we envisioned the long breathing patterns primarily as a pacing metric; a way to hold us back in our efforts, yet do so while encouraging quick feet and good running form. Over the past year or two, as we have researched running, respiration, and training modalities, we gained certifications in Heart Rate Variability (HRV), Polarized Training (a.k.a., the 80/20 method), breathwork, and became a Certified XPT Performance Breathing® Coach.

What we have learned through this process is that the benefits of deep, controlled breathing while running at a relaxed pace were far beyond our expectations! Yet even as impressive and extensive the performance gains are, it’s still a matter of basic physiology. All the hype in the world won’t make the improvements appear if the fundamental aspects of training aren’t in place. A good, full night’s sleep; a healthy balanced diet; LOTS of reasonably low-effort, long duration training spiced with bouts of High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT); and most of all, consistency. On ALL of these. These are the things which make us perform at our best.

Human Performance Specialist Robert Wilson says, “When identifying indicators you might choose to help you pilot your health and performance more effectively I recommend asking the following: Is it valid? Is it reliable? Is it accessible?”

Well, let’s apply these metrics to the Breath Runner Method and see where we stand.

Is the Breath Runner Method valid? I think so, and while there’s no studies that we can find that directly relate to it, it does seem that there is good scientific evidence to suggest that we’re at the very least heading in the right direction. A recent study published by Dr. Eric Harbour, MSc, and his team from the Department of Sport and Exercise Science, University of Salzburg, Austria, entitled Breath Tools: A Synthesis of Evidence-Based Breathing Strategies to Enhance Human Running, states, “While direct experimental evidence is limited, diverse findings from exercise physiology and sports science combined with anecdotal knowledge from Yoga, meditation, and breathwork suggest that many aspects of breathing could be improved via purposeful strategies.” This is an expanding field of research, with new tools becoming available to make it possible to do testing of the various metabolic parameters in real time without adversely affecting performance while the test is ongoing.

Is the Breath Runner Method reliable? How reliable is your ability to breathe while running? There are no batteries that need to be recharged, no software to download, no WiFi, Bluetooth, or cellular connection required. All you need is your running shoes. You don’t even need a watch, although the Breath Runner Method training plans use time rather than distance for the vast majority of workouts. Only the long runs of the Half Marathon and Full Marathon training plans (and eventually the Ultramarathon plans we will be producing soon) use a fixed distance. It has been our experience that once accustomed to Breath Running, the shifting between the various modalities is rather intuitive. It is also our contention that by giving what we feel is a better, more actionable pacing metric which encourages good running form, it decreases the incidence of running related injuries, and therefore allows for more consistency in training (but this is speculation on our part, pending studies).

Is the Breath Runner Method accessible? Is it limited to a certain class of runner? Is it bound by strict rules or limitations which define its usefulness? Can it be used by para-athletes, neurodiverse athletes, or athletes facing other challenges, whether physical, mental, emotional, or a combination of all three? We have found it useful for ALL. We have had Breath Runners who are world-class para-athletes. We have introduced it to kids. We have used it with Run-Walkers. Again, strap on your sneakers and go run. Settle into the rhythm of the pattern needed/chosen, and go enjoy yourself. What if your mind wanders and you lose track of your breathing pattern? So what? It’s a metric; it’s there for a purpose, to be sure, and the more it’s used, the greater its effectiveness, but in the end, it’s a means to a goal. It is not THE goal!

Are there other ways to strengthen one’s respiratory muscles? Absolutely! Are they valid? Yes, but then again, buyer beware. To select the most appropriate device, it is also necessary to consider one’s specific health condition, the nature of the respiratory impairments (if applicable), and the purpose of the training. Respiratory Muscle Training (RMT), also known as Inspiratory Muscle Training (IMT) — breathing through a device which restricts airflow — has been shown to help with “intermittent” sports (like soccer, lacrosse, or other sports which require short bursts of high intensity running and lots of walking and easy running), but it remains unclear if it’s useful for endurance sports, where it’s primarily low to moderately hard exercise for a prolonged period of time. Then again, it’s been shown that HIIT training is an effective way to build respiratory muscles. So is yet another gadget needed? Even health professionals are sometimes overwhelmed by the amount of disparate and conflicting information out there. It’s no wonder, since the Health and Wellness industry is a $4 Trillion business (TRILLION!! With a T!). The level of misinformation is legion. And we haven’t even touched on the issue of Artificial Intelligence (A.I.), and what it’s impact has been in it’s very short existence so far, and what it means moving forward. We’re not Anti-AI, but we’re not using it to pump out a thousand social media posts a week, either. We are, however, moving forward, cautiously.

We feel we can say with confidence that the Breath Runner Method works. Beyond the inherent respiratory muscle training that’s “baked in” to it, Breath Running helps us settle into the appropriate effort level, given the environment of the day, and given the physiological challenges we may be facing. It helps train us to run with quick feet, even at an easy pace, which is proven to reduce impact forces. Less impact on bones, joints and tendons means less recovery time between runs, which enables a more consistent training schedule. More running means the better we hone our running economy, which allows us to run faster with less effort. Notice the lack of advertising on our website. We’re on social media, but we’re not blasting into every fifth frame while one is enduro-scrolling™ (insert LOL emoji here). We have some things to sell, but we’re not shopping for yachts, yet. We like our gadgets too. We just don’t want to be messing around with them while we’re running, and we certainly don’t want to be incapable of running if we don’t have them available. We don’t need to make up a bunch of crazy half-baked claims to hype the Breath Runner Method. We’re confident that if you try it, you’ll like it. We’re just trying to do a better job of explaining how it can help your running.

Welcome to Breath Runner — it’s like running on air!

The Peter/Paul Principle

When we run, we engage a massive amount of skeletal muscle, provoke enormous hormonal action, and light up our entire neurological network. When we are running, throughout our body there is a never-ending stream of trade-offs happening between energy stamina versus fatigue resistance, muscular power versus endurance strength, and core-system regulatory function homeostasis versus survival instincts, all developed across the millennia by the evolutionary process. But as we have previously noted, the body is biased towards doing the least amount of work possible for the most result. Accordingly, distinct controls over, and adaptations to, endurance and strength-based activities have evolved in humans.

Running takes a toll on the body. But to whom does that toll get paid?

When we run, we engage a massive amount of skeletal muscle, provoke enormous hormonal action, and light up our entire neurological network. When we are running, throughout our body there is a never-ending stream of trade-offs happening between energy stamina versus fatigue resistance, muscular power versus endurance strength, and core-system regulatory function homeostasis versus survival instincts, all developed across the millennia by the evolutionary process. But as we have previously noted, the body is biased towards doing the least amount of work possible for the most result. Accordingly, distinct controls over, and adaptations to, endurance and strength-based activities have evolved in humans. We’re not going to go over the entire litany of physiological actions in running here. We’re going to focus on our respiratory muscles, and the critical role they play in our running performance. Or, more precisely, the role they play in our inability to have the running performance we desire.

Quick recap on the aerobic process in running. We take a breath. Air filters down into the alveoli, the microscopic balloons in our lungs where the exchange of oxygen (O2)and waste gases, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), occurs. The oxygen molecules travel via red blood cells (RBCs) through the bloodstream down to the muscle fibers, where they are absorbed into the cell’s mitochondria, the powerhouse of the muscle fiber. The mitochondria uses O2 and glucose, the most basic form of sugar, to power the reactions which cause the muscle fibers to move. This chemical reaction creates waste products, mainly CO2 and water (H2O). These waste gases are dispersed back into the bloodstream to be expelled by the body via the lungs.

Two things to note in the preceding paragraph: One, how the process of aerobic respiration starts. We take a breath. Two, the location of the muscle fibers to which the O2 molecules travel is not disclosed. Are these fibers we’re talking about in the leg muscles? The chest? The heart? The answer is, of course: All Of The Above. Every single muscle fiber in our body, from our head to our toes, goes through this same exact process (also note we’re sticking to the aerobic process only - things get complex as we move into the anaerobic realm). So it’s these two primary functions — the act of breathing and how it powers aerobic muscular respiration while running — where we’ll be focusing our discussion.

So to begin, let’s take a look at the physiology of our respiratory system. There’s two channels by which air enters our lungs: our nose and our mouth. Both channels empty into the trachea, which then branches out throughout the lungs into ever smaller and smaller channels, until the air that is pulled in reaches the alveoli. What is interesting is this evolutionary dual-channel design; we can choose which route we wish to have the air enter and exit. We can even choose both paths simultaneously.

It is known that for daily living, the most beneficial way to breathe is by inhaling through the nose. This has a number of important benefits for our health, such as filtering the air before it gets down to the lung tissue, warming and humidifying the air so that it matches the ambient conditions within the lungs, and nasal breathing generates nitric oxide (NO2), also known as Laughing Gas at the dentist office. Nitric oxide relaxes and expands the blood vessels, allowing the heart to pump more oxygen-carrying blood cells throughout the lung tissues. It has also been shown that by breathing through the nose, we increase the lung’s capacity to absorb oxygen due to the added pressure resistance.

All good things come to an end eventually, and it’s no different with nasal breathing. When running, at a certain point, our metabolic demands overwhelm the ability of nasal breathing to take in enough oxygen to meet demand. This is the point when mouth breathing becomes dominant. Again, it must be stressed that at this point, which for most occurs at or slightly above the first ventilatory threshold (VT1), while there is a slight increase in demand for oxygen by the muscles, it is actually the need to get rid of carbon dioxide and other waste gases that is driving the demand for faster and/or deeper respiration. While there are some individuals who have adapted to and are comfortable in breathing exclusively through their nose, even at maximal effort, these individuals are the exception to the rule. We at Breath Runner encourage as much nose breathing as practical, but do not want anyone to artificially limit their performance on the basis of some influencer’s recommendation, no matter how well-intentioned. Keep in mind, that if nose breathing was the End-All Be-All Greatest Way to Breathe Ever For All Things, we would have evolved with completely separate respiratory and digestive tracts, like dolphins and whales did. But we didn’t, and need to respect the fundamental realities of our body’s needs when we’re pushing the limits.

That being said, it’s equally important to understand that that “running out of oxygen” feeling when we’re pushing ourselves to our limits is NOT actually a lack of oxygen! It’s a overwhelming build-up of carbon dioxide in our bloodstream, and it is our tolerance to that, as well as the accompanying acidification, which ultimately determines both our ability to nose breathe as long as possible, as well as the amount of time we will be able to spend at our upper limit. It is in THESE dimensions of aerobic performance — our CO2 tolerance, and our lung capacity — where we feel the Breath Runner Method excels. Let’s dig in to see how.

Read the full article in the Breath Runner Club!

Get unlimited access to articles, videos, and more!

Cross-training for Runners

Cross-Training for Runners

What is Cross-Training? And why should I care?

What is Cross-Training? And why should I care?

The Breath Runner Method strongly advocates cross-training as part of every run training program. What exactly is “Cross” training? How does it work? “I just want to run; shouldn’t I just stick to doing that?” some athletes may say.

Cross-training simply doing something other than running on days where no running is scheduled. It’s encouraged that the activity is something that does NOT put a lot of strain on the skeletal system. Running does more than enough of that, thank you, and that’s why days “off” in-between runs are called for. But we still want to work our cardio-vascular and muscular systems, so doing an alternative activity like swimming, biking, yoga, strength training, or similar can be beneficial. Keep in mind that we still need to take a day off (sometimes two) from ALL activity, just to allow the body to recover. Let’s dig into the nuances.

Swimming is considered by some to be the ultimate cross-training activity for runners, as there is zero skeletal impact (unless you swim into the wall, but we’ll assume that that won’t be an issue). Swimming is a “full body” activity, since both the upper body (arms and chest), lower body (legs and hips), and core (which I define as everything between the knees, elbows, and neck) are engaged. The problem for most who identify as a single-sport run athlete is that the aquatic environment is an alien world where the laws of physics goes sideways, and the their body seems to go in only one direction: down. It doesn’t have to be this way, and AquaTerra Coaching has the program and knowledge to help those who have no swim experience.

One of the unique aspects of AquaTerra Coaching’s swim training is an emphasis on breathwork as well. This isn’t surprising, once you learn that the Breath Runner Method was borne out of AquaTerra Coaching swim experience. Yet the journey of discovery that the Breath Runner Method created has given new depth and meaning to AquaTerra Coaching’s program. Swimming creates unique challenges for the athlete which is not familiar with the entrained breathing patterns that swimming demands. Because of the head-down, face in the water nature of swimming freestyle, we have no choice but to sync our breathing with our arm cadence. For someone who is used to breathing “on demand” (“I’ll breathe when I want, how I want, as much as I want!”), this limitation to their breathing pattern can cause a host of issues with their swimming.

Swimming is widely considered the most technically demanding sport because of the dynamics involved with trying to self-propel through water. By far the biggest factor is drag; water is nearly 800 times more dense than air, so every little thing that we do that causes unnecessary drag in the water is magnified to ridiculous proportions. Olympic level swimmers can spend years fine-tuning their swim stroke to gain one or two seconds on their best time. Not minutes; seconds. Often micro-seconds. Take notice of your three longest fingers for a moment: the distance between the tips of the fingers is often the distance which defines 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place in an championship swim event. The level of finesse in technique required to perform at this level is mind-boggling.

So what hope is there for a runner who can barely make it from one end of the pool to the other without drowning? There’s more than hope — there’s a entire new world of adventure awaiting, once the fundamental aspects of swimming are understood and implemented. And for most, the key component is their breathing. That “Out of oxygen” panic feeling that we experience when we’re at our limit in the water? It’s not a lack of oxygen. It’s an intolerance to CO2 buildup in our bloodstream. It’s the same exact phenomenon we deal with in running, and it’s learning to tolerate the intolerable (within reason) that is what spawned the creation of the Breath Runner Method.

But in the water, there is an added dynamic which causes us a spot of bother. It is, in a word: water. Our bodies are on average 60% water, yet our respiratory system, which can expel up to 1500 ml of water per day when exercising at high altitude, is entirely intolerant of water in its liquid form. This causes most novice swimmers to do the worst possible thing: Hold their breath while trying to swim. Try running 200 meter threshold repeats, but only taking one inhale and exhale on every 8th or 10th step; hold the breath in-between those ultra-fast gasps for air. How long do you think you’ll last? Yet this is what people who don’t know how to swim properly end up doing. It’s not their fault. We all have this pre-historic part of our brain which I like to call our Lizard Brain; it’s the part of our evolutionary structure that developed when we crawled out of the pond and traded gills for lungs. No longer having the ability to breathe while underwater means that when we submerge, our Lizard Brain immediately wants us to hold our breath until we resurface. This is a phenomenon known as the mammalian dive reflex. Overcoming this reflex for the aquatically unfamiliar is HARD; this is a hard-wired physiological survival response. Yet it can be overcome with proper training. And the key to overcoming this obstacle? You guessed it: Breathwork. Much more on this topic will be found on the AquaTerra Coaching website soon!

Want to work on your swimming without having to worry about breathing in water? The Vasa Erg is an excellent cross-training tool! And AquaTerra Coaching can offer discounts on new Vasa Ergs, Vasa Trainers, and more for your swimming needs!

Copyright 2025 © AquaTerra Coaching, LLC

Read the full article in the Breath Runner Club!

Get unlimited access to articles, videos, and more!

Copyright 2025 © Breath Runner

Foundations of Training

The foundations of training, also known as the Base Building period, is a lot like pouring concrete for the foundation of a house. The plot thickens…

The foundations of training, also known as the Base Building period, is a lot like pouring concrete for the foundation of a house. The plot thickens…

A foundational element of the Breath Runner Method are low effort runs done with long breath patterns, usually 9-Step or 7-Step patterns. These runs are appropriately termed “Foundation Runs” in our training plans. They appear frequently during the base building period of all our plans, and for good reason. Entrenching this fundamental structure into one’s physiology pays HUGE dividends later in the year when the “A” race in suddenly at one’s doorstep. As the old saying goes, “Take the time to make the time to have the time to enjoy your time.”

As we have stated in the Breath Runner Method Handbook, this is NOT a “7 Minutes a Day to Your Fastest 5K!” kind of program. We’re not making extravagant claims promising instant results. Far from it; it will take WEEKS before substantial improvements in running is realized using this program. That is by design. The Breath Runner Method consists of training consistently, at appropriate intensities, with proper hydration and nutrition practices, while connecting breathing to cadence. Simple, straightforward, and succinct.

Yet, there is a problem with these Foundation runs; for some, it’s a BIG problem! The problem is: my Ego is not my Amigo! Foundation runs are not sexy. They’re (usually) not impressive. They’re not exciting. They are low, slow runs, often for a long, long time. Other runners may pass us. Little kids may pass us. Old people may pass us. It seems like the whole world is faster than us! And yet, this is what we need. I’ve written before about Slow Growth to Fast Running, and I’ll probably keep repeating myself on this subject, simply because it’s that important. But I’ll let some real experts weigh in on the topic.

Seiler KS, Kjerland GØ. Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: is there evidence for an "optimal" distribution? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006 Feb;16(1):49-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.00418.x. PMID: 16430681.

Read the full article in the Breath Runner Club!

Get unlimited access to articles, videos, and more!

When is it Too Cold to Breath Run? (Copy)

When temps get extreme, too much of a good thing becomes a bad thing

NOTE: This Journal entry is publicly available, because the information is too important to paywall.

When temps get extreme, too much of a good thing becomes a bad thing

NOTE: This Journal entry is publicly available, because the information is too important to paywall.

Image found on Internet; origin unknown

This past week has seen historic severe winter weather all across the continental US. A massive polar vortex has unleashed extreme cold air that has created blizzard conditions in southern Gulf coast, a week of temperatures 10 to 25℉ below historical average, and created an emergency blood shortage (please donate!). On one hand, this shouldn’t really be that big of a surprise; January is the coldest time of year for a majority of the country. On the other hand, a series of mild winters the last few years has lulled many of us runners into a state of… not necessarily complacency, but perhaps a bit of a routine where dealing with severe winter weather wasn’t too great of a concern.

Well, now’s the time to be concerned. We’re not going to go into clothing and shoe options, and other such details, as there’s already plenty of great information out there on these topics. What we are going to focus on is the issues involved with exercising in extreme cold temperatures. As Professor Myra Nimmo from the School of Biosciences at the University of Birmingham, UK, states: “To plan for a performance in the cold requires an understanding of the mechanisms underpinning the physiological response.”

And this cuts to the heart — or should we say lungs — of the issue. The Breath Runner Method is all about taking steady, deep inhales of air while running. When does that become a problem? Dr. Michael Kennedy, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, cautioned, “If it’s a really cold day, a high-intensity run or ski could change your life.” And not for the better. Extreme cold causes extreme impacts to the body, and the body reacts with extreme responses.

When we breath in extremely cold, dry air while running, this evaporates the water from the airway epithelium, the surface of our bronchial tubes. As the epithelium dehydrates, it causes changes in airway wall structure and function. This damage triggers a release of histamine, an inflammatory mediator, which causes the smooth muscles of the bronchioles to constrict. This swelling makes it hard to breathe — it’s literally exercise-induced asthma. In a worst-case scenario, this could lead to permanent airway damage. "The inflammatory response is so large that the lungs never recover back to a healthy baseline," according to Dr. Kennedy, "They basically remodel." Additionally, the dehydration of the airways causes the body to respond by increasing mucus release. If the dehydration is severe enough, it can cause the mucus to be thicker, making it harder to clear. This combination of the sinuses and upper airways getting dried out and the smaller lower bronchioles getting inflamed and gummed up with thick mucus is a recipe for disaster.

Image found on Internet; origin unknown

But again, the key question is: How cold is too cold for running? The answer is, of course: It depends. How well adapted are you to the cold? How susceptible are you to Exercise-Induced Bronchodilation (EIB; otherwise known as Exercise-Induced Asthma)? How long and how hard are you planning on running? What are you wearing? How old are you?

By and large, running in cold weather has tremendous health benefits. But here we’re not talking about “normal” cold — we’re talking about extreme cold, where health risks start increasing exponentially with every drop in degrees. As the temps plummet, most of the body’s energy is used to maintain core temperature. To conserve heat, blood flow is re-directed away from the skin and extremities towards the chest and abdomen (core). However, we’re running, so a LOT of bloodflow is going to the working muscles in the legs. The higher efforts of running are helping keeping our internal core temperature up. Presumably, we’re dressed appropriately for the weather; our extremities are covered, and therefore we’re good, right? Not necessarily.

If we normally sweat easily, we can quickly saturate even the best high-wicking cold weather running gear. In extreme cold, the sweat can freeze on the outer layer of the clothing, which will reduce our performance. Stay out there long enough in those conditions, and the surface chilling can become a source for hypothermia - the cooling of the body’s core temps. The more our core cools, the worse our run becomes. Dr. Phillip J Wallace of the Environmental Ergonomics Laboratory, Department of Kinesiology at Brock University in Ontario, Canada, states, “Overall, simply cooling the skin impaired endurance capacity, but this impairment is further magnified by core cooling.” In other words, there is an increased risk of frostbite, and potentially hypothermia, if we stay out there too long.

Also, we’re most likely wearing a face mask of some sort. While this will offer protection for our sinuses and upper airways, remember that we’re breathing out a LOT of water vapor with our exhales, and that moisture will freeze on the mask, restricting airflow. Removing the mask makes it easier to breathe, but now we’re again subjecting our upper respiratory system to cold shock, which has been shown both increase the feeling of breathlessness (technical term: dyspnea) and coughing. For those of us who already suffer exercise-induced asthma, this additional stressor can quickly push things into dangerous realms. As the late Professor Kai-Håkon Carlsen, of the University of Oslo in Norway declared, "It is important that athletes at risk are monitored through regular medical control."

Image found on Internet; origin unknown

Yeah, but… How Cold is TOO Cold? Unfortunately, it’s not an easy question to answer. Dr. Hannes Gatterer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Mountain Emergency Medicine (Eurac Research) in Italy states, “Despite the obvious requirement for practical recommendations and guidelines to better facilitate training and competition in such cold environments, the current scientific evidence-base is lacking." What IS known — and which should be blatantly obvious — is that the longer one is in extreme cold, the greater the health risks. As explained by Dr. John W Castellani of the Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division, U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, and Professor Michael J Tipton of Extreme Environments Laboratory, Department of Sport and Exercise Science, at the University of Portsmouth, UK: “Participants in prolonged, physically demanding cold-weather activities are at risk for a condition called "thermoregulatory fatigue." During cold exposure, Castellani and Tipton explain, “the increased gradient favoring body heat loss to the environment is opposed by physiological responses and clothing and behavioral strategies that conserve body heat stores to defend body temperature. The primary human physiological responses elicited by cold exposure are shivering and peripheral vasoconstriction. Shivering increases thermogenesis and replaces body heat losses, while peripheral vasoconstriction improves thermal insulation of the body and retards the rate of heat loss. A body of scientific literature supports the concept that prolonged and/or repeated cold exposure, fatigue induced by sustained physical exertion, or both together, can impair the shivering and vasoconstrictor responses to cold,” which creates thermoregulatory fatigue. As our body loses its ability to maintain central thermoregulatory control, we face an increased susceptibility to hypothermia.

This phenomenon has been termed “Hiker’s hypothermia”, which is basically the polar opposite (pun intended) of the “Boiled Frog” analogy. The increased strain of the extreme temperatures coupled with the already high level of stress induced by running can conspire to impair our ability to accurately judge the level of danger we are subjecting ourselves to. And it doesn’t have to take a long time for this to happen when the temps are low enough. Jiansong Wu, Dean of the School of Emergency Management & Safety Engineering in Beijing, China, notes, “The high physiological strain at the very beginning moment of cold exposure can significantly affect the ability to make correct judgment and action." In other words, don’t be a hero. There’s very few of us out there who are truly adapted to running in sub-zero ℉. And even for those who are, Dr. Castellani notes, “The few studies that have been done suggest that aerobic performance is degraded in cold environments.”

Specific to the Breath Runner Method, there’s important paradoxes about exercising in the cold of which we must be aware. Not the least of which is: it’s easier to go harder, and that’s not always a good thing. As Dr. Oleg V. Grishin, of the Research Institute for Physiology in Russia states, "Under cold conditions the decrease of energy expenditure is the natural phenomenon." The less energy expended, the more available to do the work! But it’s exactly this phenomena that can lead to trouble.

Image found on Internet; origin unknown

Thomas J. Doubt, of the Naval Medical Research Institute’s Hyperbaric Environmental Adaptation Program in Bethesda, MD, cautions, "Ventilation is substantially increased upon initial exposure to cold, and a relative hyperventilation may persist throughout exercise." So even though we feel like it’s easier, our body - especially our respiratory system, is in over-drive. With prolonged exercise, he notes, “ventilation may return to values comparable to exercise in warmer conditions. The oxygen demand of exercise is generally higher in the cold, but the difference between warm and cold environments becomes less as workload increases. Heart rate is often, but not always, lower during exercise in the cold.” Sounds OK, right? Ready to boil that frog yet? Think about it, and again, we’re talking about extreme cold — it feels relatively easier to run in the cold from an exertion standpoint, but we’re also using a greater amount of oxygen to do the work, which requires a higher breathing rate, which is subjecting our respiratory system to greater stress.

Linda Eklund of the Division of Medicine at Umeå University in Sweden discovered, “Elite cross-country skiers are regularly exposed to cold, dry air and have a high prevalence of asthma compared to the Swedish population. Heavy exercise during cold air exposure at -15°C/5°F induced signs of an airway constriction to a similar extent as rest in the same environment. However, biochemical signs of airway epithelial stress, cytokine responses, and symptoms from the lower airways were more pronounced after the exercise trial." In other research, she concluded that healthy individuals performing short-duration moderate- and hard-intensity exercise in sub-zero temperatures responded with lung function changes and an increased airway permeability (structural changes of the airway wall which result in its thickening from scar tissue, airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR), and potentially a progressive irreversible loss of lung function).

Dr. Eike Marek of the Institute for Prevention and Occupational Medicine at the Ruhr University Bochum has found that athletes who exercise in extremely cold air have “changes in the lung epithelial cells caused by inhalation of cold and dry air." His research found that the water vapor of exhaled breath in extreme cold air conditions contains a number of chemical markers, including hydrogen peroxide, which is described as an indicator of airways inflammation. “The concentration and release of hydrogen peroxide increased after exercise in cold air, [which] points to an increase in inflammatory and oxidative stress.” Researchers from Beckett University and Trinity University, both in Leeds, UK, found that in cold temperatures, oxygen requirements for exercise was significantly higher than in warm conditions. This increased oxygen demand at the same exercise intensity ultimately leads to an earlier onset of fatigue, and possible early cessation of exercise. This could seriously heighten the risk of hypothermia if we’re out running in the trails, getting good and sweaty, and then find we have to start walking. It doesn’t even need to be extreme cold for this to be an issue. Core body temperatures as low as 33.3°C/92℉ have been observed in 18.3°C/65℉ conditions.

So the danger is: very cold air makes it easier for us to go harder, because the need to keep the body’s core temperature up over-rides our uncomfortability of being in the cold. But in extreme cold, high efforts which require deep breathing to power the muscles may cause damage to the respiratory system. Your lungs won’t freeze, but push it hard enough, and they’ll never be the same. Dr R J Shephard, Professor Emeritus of Applied Physiology at the University of Toronto, Canada cautions, “An increase in the intensity of physical activity may be counter-productive because of increased respiratory heat loss, increased air or water movement over the body surface, and a pumping of air or water beneath the clothing. Shivering can generate heat at a rate of 10 to 15 kJ/min, but it impairs skilled performance, while the resultant glycogen usage hastens the onset of fatigue and mental confusion.”

Image found on Internet; origin unknown

There’s other aspects to extreme cold to which we must acknowledge. Dr. Gordon Giesbrecht, also known as ‘Professor Popsicle’, who runs the Laboratory for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at the University of Manitoba, Canada, cautions, "Cold exposure also elicits an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance." In other words, it’s not just our respiratory system that’s working harder. Our heart is under increased strain. Dr. Tiina Ikäheimo of the Center For Environmental and Respiratory Health Research at the University of Oulu, Finland, found that exercising in extreme cold often "augments cardiac workload in persons with coronary artery disease more" than it does in relatively benign temperatures. Dr. Alan Ruddock, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Sport Physiology and Performance at Sheffield Hallam University, UK, wrote the chapter on Physiology and Risk Management of Cold Exposure in the book Extreme Sports Medicine. He minces no words: “Declining body temperatures are associated with reduced dexterity, shivering, poor muscle co-ordination and force production, amnesia and cardiovascular strain that might challenge human survival let alone performance.” When’s the last time you had a cardiac stress test done?

Running in extreme cold AND at altitude compound the risks. Researchers at the Sport Mountain and Health Research Centre, University of Verona, Italy found that when compared to single stress exposure, exercise performance and physiological and perceptual variables undergo additive or synergistic effects when cold and hypoxia are combined. Once again, the more extreme the circumstances, the risk factors don’t multiply — they increase exponentially.

Age is yet another factor that can’t be dismissed. Dr. Liron Sinvani, M.D., an associate professor of medicine at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, NY notes, as we age, most people tend to lose muscle, a condition known as sarcopenia. Muscle density provides insulation and generates heat. Older adults are also more likely to have thinner skin, making it easier for heat to escape, as well as decreased blood flow in the skin. “All of these things culminate in a reduced ability to regulate their body heat,” putting them at greater risk for danger in cold weather, Dr. Sinvani explains. Of course, if we stick to a well-balanced run training program which includes strength and conditioning exercises, we can help reduce our risks. As researcher Juhani Smolander of the ORTON Research Institute in Helsinki, Finland, found, while enhanced aerobic fitness may not give additional protection against core cooling in the elderly, it did seem to attenuate older subjects' heightened blood pressure response to cold."

Another aspect of extreme cold that not many runners think about: what happens to our sneakers? Researchers at the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the Mayo Clinic Sports Medicine Center in Rochester, MN found that the colder it gets, the more significant the reduction of shock attenuation in most commonly used running shoes. Their conclusions are fairly blunt: “These findings have important clinical implications for individuals training in extreme weather environments, particularly those with a history of lower limb overuse injuries.”

Again, and this can’t be stressed enough — You Do You. There are a whole host of known benefits to running in cold weather. But when the temperatures start to get extreme — it’s generally acknowledged that temperatures below -15°C/5°F qualify as extreme — it’s time to start questioning one’s rational for running in those conditions. As I often tell my Age Group athletes, if your mortgage isn’t dependent on the results of your next race, chances are you’re better off doing something a bit less strenuous.

Image found on Internet; origin unknown

Satan’s Sidewalk

A unique feature of the Breath Runner Method is that it does NOT dictate a pace or heart rate value to designate a given training zone. Something that never really gets talked about by most who talk about training zones is that by virtue of our being carbon-based bipeds in an ever-changing environment, the metabolic breakpoints of VT1 and VT2 are ever variable, defying precise, fixed numerical values. There are dozens of influences, both internal and external, which can change the numbers on a day-to-day basis (and even minute-by-minute basis in extreme situations).

How to pace yourself when pace doesn’t matter

In our previous post, we touched on using the Breath Runner Method while running on a treadmill. Let’s dive into that specific topic a bit more intently, in order to gain a better understanding of what the goal(s) of the Breath Runner Method really are.

The basis for all endurance training comes down to two things: VT1 and VT2. “VT” stands for Ventilatory Threshold, a point at which the body shifts gears on how it responds to increased effort. Obviously, there are two threshold points. Below the first Ventilatory Threshold (VT1), the body is primarily using fat as its preferred fuel source. This is a highly sustainable and metabolically efficient way to create power for the muscles, but it’s also a bit time consuming, all things being equal. As efforts ramp up, the need for more fuel coming in more rapidly ramps up as well. This “breakpoint” as it’s known, is where muscle glycogen starts becoming the favored fuel source. While it’s quicker for the mitochondria — the muscle cell’s power generation factory — to grab and burn, it's also metabolically dirtier. That means that the amount of time we can sustain such effort changes from hours (below VT1) to tens of minutes (above VT1).